- April 8, 2025

Do you remember what the widely publicized financial market concern was before the COVID-19 pandemic began? Neither did I until I looked it up. It was the “Inverted Yield Curve”. I’ll spare you all the mundane details, but this is when the interest yield on the 10-year Treasury is less than that of the 2-year Treasury. Normally, it is the opposite and many market prognosticators believe the inversion foretells impending economic weakness.

The concern before that? There were several minor ones, but the one that received the most publicity was the Federal Reserve raising interest rates too quickly. Why did they do that? The economic engine was humming along pretty well and no longer needed as much assistance. Very concerning, I know.

It goes without saying that the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on markets and economies around the world is not something that will soon be forgotten. It rightfully caused great concern – not only about economic conditions but also our overall well-being. But unlike the two concerns cited above it wasn’t forecasted and discussed on CNBC for six months before it happened. The events or forces that actually cause significant market dislocations aren’t the ones that people are talking about.

This brings us to the latest chief concerns – rising interest rates and inflation. For those keeping score, history is once again repeating itself as the prospects of higher interest rates are front and center. Economic damage from the pandemic still persists around the world, but there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Interest rates have risen as fears of recession have subsided and an outlook for growth has returned. Maybe there was a hope that if we just get through the pandemic and it’s economic fallout, we can catch our breath for a while before the next thing.

Unfortunately, that is not the world we live in – it’s on to the next one. There’s always something we’re supposed to be concerned about. Rarely, though, are they things worth acting on (please read to the end for the epitome of things not worth acting on) by adjusting your portfolio.

Psychiatrist, author, and Holocaust survivor, Viktor Frankl observed that we can’t control our circumstances but we can control our attitude and reaction to a given set of circumstances. I might take that one step further when it comes to investing and add that we can prepare ourselves to have a positive attitude and reaction to a given set of circumstances through planning for various circumstances.

Interest Rates and Bonds

As the economic concerns of the pandemic have begun to subside, the attention has shifted to an increase in interest rates and a growing concern about inflation given the amount of stimulus infused into the economy to support recovery efforts. These certainly represent changes from recent experience – not too long ago the concern was more about whether or not US interest rates would turn negative (less likely as time passes) and if economic weakness would lead to deflation.

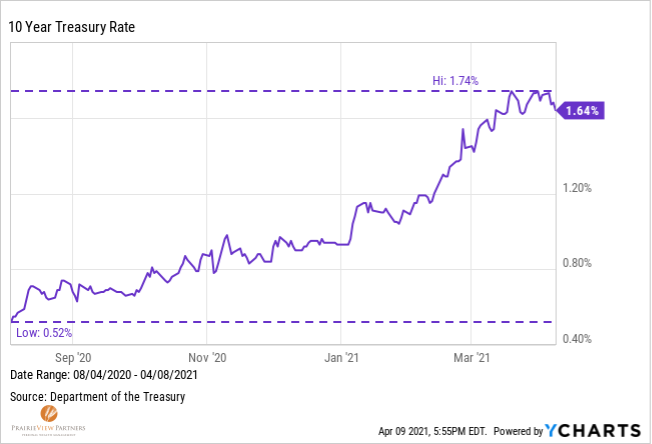

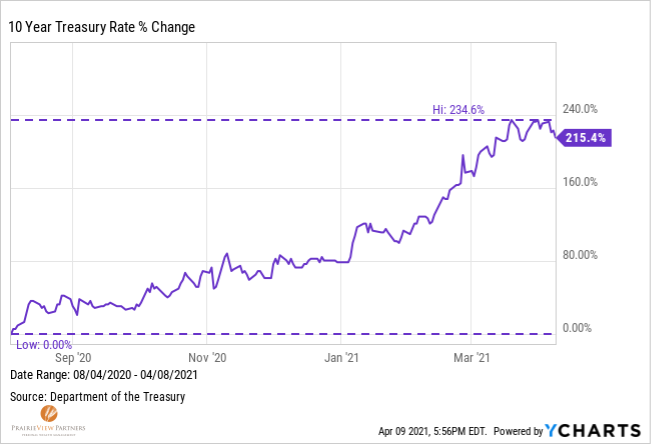

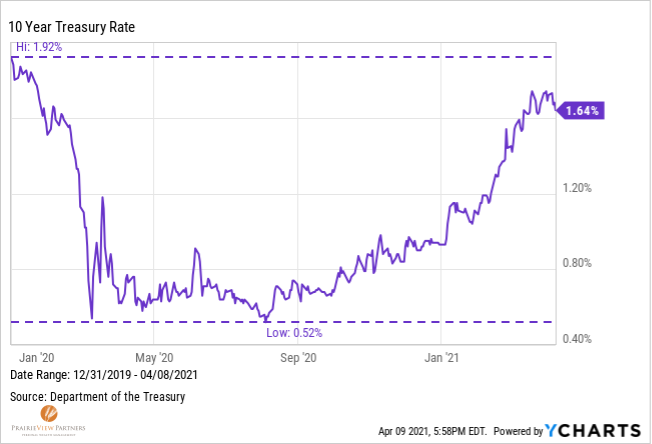

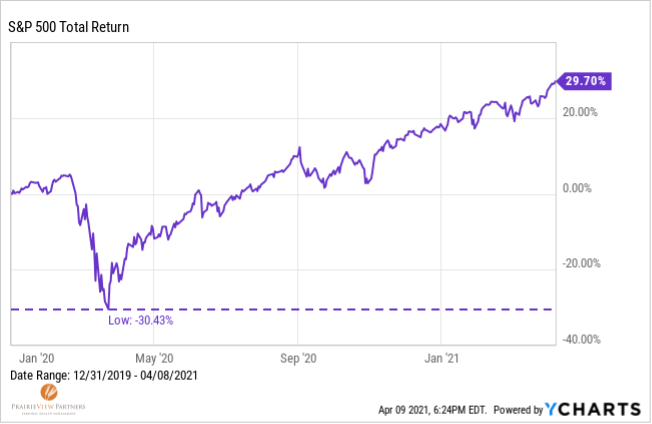

As with most things, context matters and these should be evaluated with a little wider lens. The 10-year Treasury rate has increased from a low of 0.52% in August 2020 to 1.64% today. That’s a 215% increase!

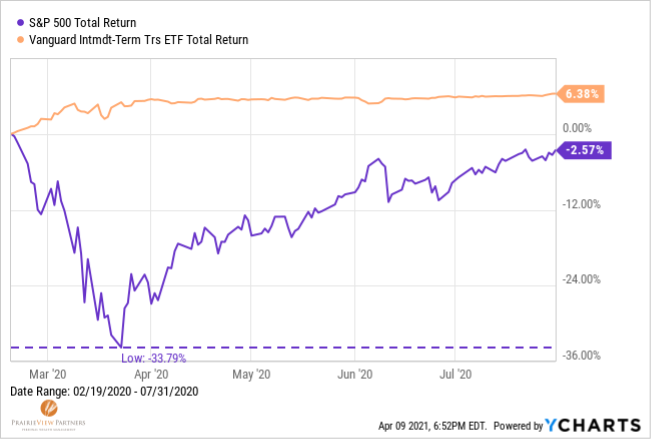

If we expand the lens, we’ll see that the current rate has not yet risen above where it stood at the beginning of 2020. As economic concerns from the pandemic overwhelmed markets and drove stock prices down, demand for Treasuries soared and drove prices up and yields down (reminder: when bond yields decline, their prices rise). This is the textbook definition of the benefit of allocating one’s portfolio between stocks and bonds.

The 10-year Treasury yield bottomed on August 4th, 2020 at 0.52%. About a week after that, the S&P 500 reached it’s early 2020 high to recover its entire decline. Since then, the total return of the S&P 500 has been 26% while the total return of the Vanguard Intermediate Treasury ETF (VGIT) has been -3%.

It was almost as if last August Treasurys said to stocks, “Alright, we carried you for a while, but now it’s your turn”. This is about as close as we ever get to how the finance textbooks tell us stocks and bonds are supposed to work together. As the outlook for economic growth improved, investor risk-taking returned and drove stock prices and interest rates to rise and in turn bond prices fell. On the plus side for bonds, the future returns they offer now are higher than they were in August.

Beware the Comparison…or Lack Thereof

The outlook for economic growth continues to improve. Last week the Wall Street Journal’s panel of top economists increased their average GDP growth outlook for 2021 to 6.4%. Aside from the grain of salt that should be taken with all economic forecasts with level precision, the other notable thing from the article on these findings is the absence of data marking the low point from which this growth is built upon.

That remarkable growth rate and the expected 3.2% growth for 2022 – lower but still above trend – put the US economy on a path to return to 2019 GDP levels in or around 2023. The employment recovery is seen following a similar path; however, the permanent job losses are harder to project.

Inflation

Despite my well documented skepticism of anything resembling a prediction, I noted the above section because topics like that are starring character in recent concerns about inflation. It’s a logical conclusion to draw. Rising interest rates combined with the highest economic growth rate in nearly 40 years and rapidly rising employment may understandably put upward pressure on inflationary readings. Again, context matters.

Like GDP growth projections, year over year inflation readings for the next several months will be from exceptionally low levels. Consumer Price Index growth rates from March through July of 2020 were all less than 1%. Against that backdrop, an expected inflation reading of 3% by June this year and falling back to 2.5% by December as the comparison is less dramatic is hardly troubling.

But what about all the economic stimulus/recovery/rescue money that the government has injected into the economy? There two ways to think about this: we can consider it to be either a replacement for lost economic activity or to be additive. If this amount of stimulus had been injected in 2019, it would most certainly be additive and highly inflationary. However, in an environment where the economy was operating at less than 70% of its productive capacity and three or four trillion dollars of trend-line economic growth was wiped out, the evidence more strongly favors the replacement theory, which is less supportive of excessive inflation.

The term “excessive” provides a key distinction, which is often lost in conversations regarding inflation. An inflation rate of 3% is viewed the same as 8% inflation. Will we experience inflation in the coming quarters that exceeds that of the recent past? We can’t know for sure, but it seems likely. Will we experience the runaway inflation of the 1970s and 1980s? There are many structural differences in the domestic and global economies that make that a very remote possibility – globalization, service-based economy, decline of unions, more technology rather and fewer natural resources as inputs, to name a few.

But even 3% inflation presents a notable change after 20 years of generally less than 2% inflation and leads to the natural question of how this may impact an investment portfolio. There are two broad ways to approach this:

- Change the make-up of one’s portfolio in response to changing inflationary expectations.

- Recognize that inflation will always be a factor to varying degrees and incorporate that assumption into a portfolio in ways that position it to generate above-inflation returns over many years through the ebbs and flows of the specific rate of inflation.

Common assumptions that things like commodities, gold, or Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) are effective inflation hedges have limited success in short and long time periods. Adding or subtracting those to a portfolio in response to inflation amounts to nothing more than market-timing, which also has a spotty track-record at best. Including them as core or permanent positions in portfolios presents different challenges – most tend to under-perform stocks over many years and all present more volatility than bonds.

While it may seem simple, the portfolio comprised of a diversified mix of stocks and bonds tends to provide the most successful outcomes over varying circumstances. Stocks have an unmatched long-term track record when compared to inflation and the value that a portfolio of high-quality bonds provides during times such as February through July of 2020 cannot be overstated. From the quote above, we can’t control the circumstances in which we are investing, but we can control our response, or in some cases lack of response, to those circumstances.

Now for why you actually read this far

GameStop (I’ll use this one stock to be synonymous with the other “meme stocks” that rose to fame in January). I’ll be honest, having never been a video game player, I hadn’t heard of the retailer until it’s 15 minutes of fame earlier this year. At the same time it was one of the most amusing, curiosity piquing, and saddening investment stories I can remember. It was the perfect storm of several investment mechanisms that created millionaires out of novice traders, destroyed businesses, and caused other novice traders to lose their savings.

So, what happened? It was the culmination of several forces that individually are mostly irrelevant, but they all came together at the right time for what may be the story of the year in markets. Let’s take them one by one.

For much of the twentieth century there was a “strategy” many analysts and money managers implemented from time to time referred to as a “Pump and Dump” scheme. It was basically nothing more than leaking a story about a company or stock they owned to the press to get them to “pump” it, so the price could go up, they make a quick buck and then “dump” it. There is a scene of Bud Fox, played by Charlie Sheen, doing exactly this in the movie Wall Street. Understandably, this was deemed illegal sometime in the 1990’s. However, the democratization of information via Social Media makes it easier to spread information and more difficult to police. This occurred via an online forum that spread the word that the company stock should be bought creating the 21st century version of a “Pump and Dump”.

If it’s hard to believe that a lot of amateur traders buying a few hundred or a thousand dollars’ worth of a stock could cause what happened, you’re right. But there were also a couple hedge funds that had multi-billion-dollar short positions in the stock. A short position is a bet that a stock will fall where shares are borrowed and sold with the intent to purchase those shares, or “cover a short”, at a lower price. In this case, the shorts had overextended themselves and a modest price increase caused by the additional buyers caused the price to go up, forcing the hedge funds to cover billions of dollars of their short positions.

This massive, forced buying sent the price soaring and as it did so, other hedge funds saw the opportunity and started buying even more to add fuel to the fire. This is called a “Short Squeeze”. One of the hedge funds lost so much money on its short trade it nearly went out of business and needed to be bailed out by another fund.

Once the short positions were covered and the last amateurs piled in, buying dried up and the shares fell as fast as they rose. Some early traders on the bandwagon cashed out with amazing gains, some who were late to the party lost nearly everything they put into the stock. For most, this was nothing more than an entertaining or confusing side show. But it does highlight the perils of a lack of diversification, overextending one’s capital, and reacting to popular trades or the most recent hot topic in markets.

Thanks for reading.

Matt Weier, CFA, CFP®

Partner

Director of Investments

Chartered Financial Analyst

Certified Financial Planner®