- March 4, 2025

I recently dedicated a whole piece to why the recent “money printing” to stimulate the economy is unlikely to lead to run-away inflation. So, why am I following it up with a piece about how to invest for an inflationary environment, you ask? There are three reasons for this:

- Even modest inflation, as seen recently, will cause a significant erosion in the purchasing power of a dollar, or how much a dollar will buy you, when spread out over a 30-year investment horizon.

- Despite the majority of evidence pointing to modest to low inflation, the possibility of periods of higher inflation should not be ruled out or ignored.

- I pointed out in my last piece that while overall inflation, and the majority of individual components, are expected to see modest to low inflation, there are components such as healthcare and education that are likely to continue to see above-trend inflation. *Note: Recent reports of the pandemic’s impact on the cost of higher education are beyond the scope of this piece, as it is likely too early to distinguish between temporary and long-lasting changes.

All three of these factors can and should be considered when developing a long-term investment plan that contains many different types of goals.

Slow Erosion

Think back to high school biology. Do you remember the images of a river’s life stages? First, you see a narrow stream winding through the woods. Then, a little wider stream with less pronounced bends. And finally, you have the Mississippi. If you watch the river in real time, it’s nearly impossible to notice the erosion taking place.

Likewise, it’s difficult to notice the effects of inflation from one year to the next – especially when it’s in the recent range of 1% – 3%. The $5 loaf of bread last year that is now $5.10 is not something that you’re going to think twice about. If you switch to a low carb diet for 30 years before buying your next loaf of bread, that loaf will cost $10. You went from the winding stream through the woods directly to the Mississippi.

The (generally) slow nature of inflation from one year to the next builds over the long-term. Because of this, it is important that our investments follow a path that, at a minimum, keeps up with inflation, but ideally exceeds it. We want the $10 loaf of bread in 30 years to take the same, or smaller, bite out of our portfolio as the $5 loaf does today.

The Greatest Inflation Hedge

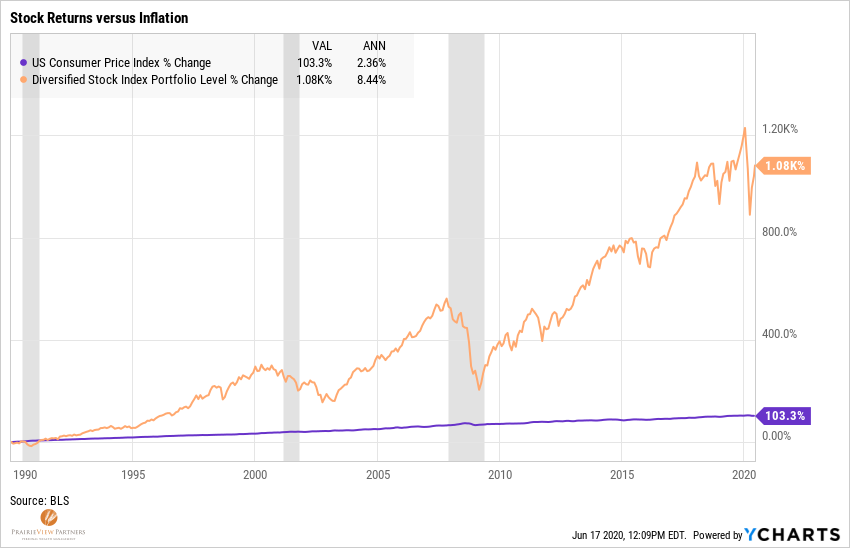

It may not come as a surprise that common stock ownership of companies from around the world has been the most successful means of compounding wealth at a greater rate than inflation. The results speak for themselves. A globally diversified stock portfolio grew approximately three times the annual rate of inflation over the last 30 years. But sometimes, particularly in times like we’ve recently experienced, it is helpful to review this long-term compounding power.

The chart above vividly depicts the results of stock returns compared to inflation. It even highlights the three recessions we’ve experienced (the shaded gray regions) since 1990 – I assume we’ll soon see a fourth one officially added soon – and how stocks have resumed growth following those recessions. Despite the results, it’s also helpful to know why this happens.

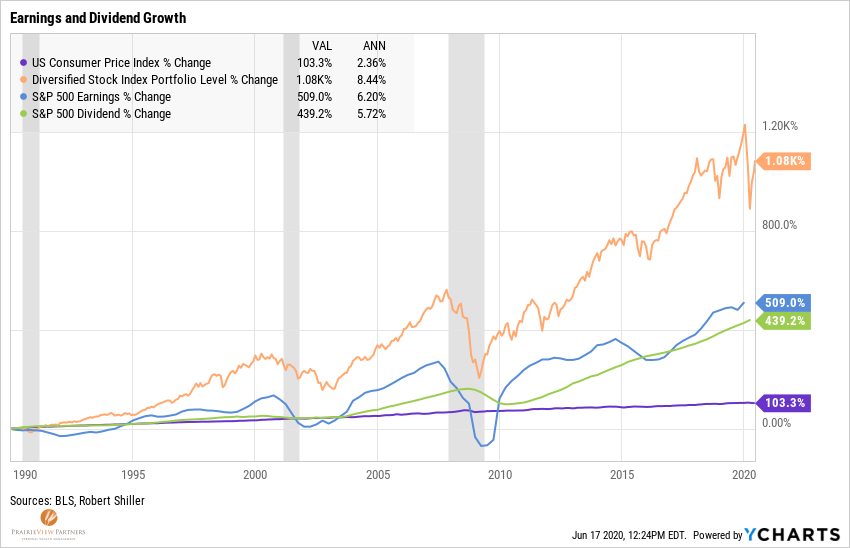

The “why” behind stocks’ return is the earnings and dividends they generate. Companies in the US and abroad have been wildly successful at growing their earnings and dividends over time and through multiple economic environments. The chart below again covers the time period since 1990. It shows earnings and dividends both growing at about double the annual rate of inflation over that time span.

The track record of earnings and dividend growth exceeding inflation extends beyond the last 30 years. Going all the way back to 1926, both have grown in excess of inflation in over 75% of all rolling 10-year periods and 100% of all rolling 30-year periods. Companies’ success in growing their earnings and dividends has driven stock returns over time and through many diverse and challenging economic environments.

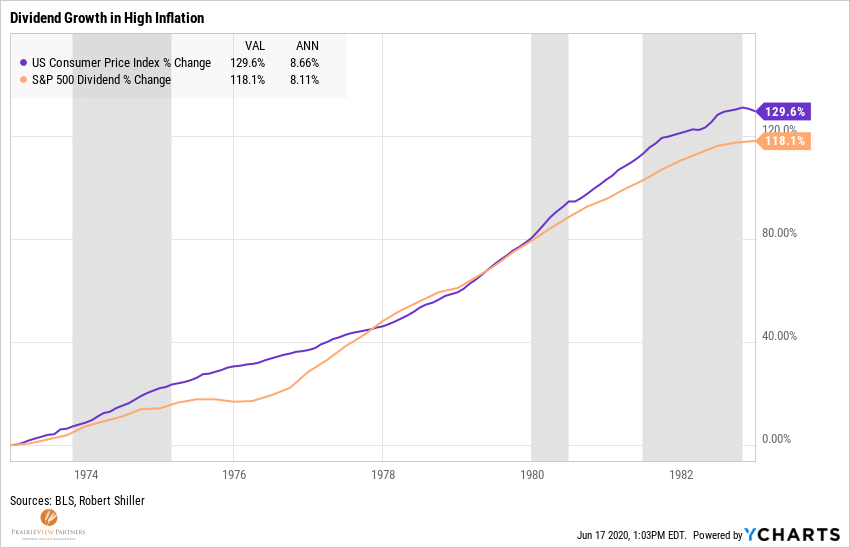

It should be noted that this successful track record includes times when inflation has been relatively steady, exceptionally high, and even rather benign, as we have seen more recently. The periods of time marked by the highest inflation may seem to present the greatest challenge. The 10 years that began with 1973 and ended in 1982 saw the highest inflation of any rolling period reviewed. While dividends didn’t completely keep pace, they performed admirably (see chart below) and by year end 1984, they pulled ahead of inflation.

In real, or inflation-adjusted, terms, that loaf of bread that nearly doubled in price over 30 years might actually only cost about half as much if paid for with dividends 30 year later. Or in a shorter, higher inflation environment, it might cost you the same amount. But it would rarely cost you more after the passage of years.

The Allure and Risk of Cash

To be clear, cash is a valuable component of a successful financial plan. It helps meet short-term obligations during periods of disruption – recent months serve as “Exhibit A” for this value provided by cash. It is also a valuable tool for saving for a goal in the near future, such as a major home remodel in the next three years, where it is not appropriate to subject those savings to market fluctuations. Unfortunately, its value and allure as a short-term tool can be mistakenly extrapolated into the long-term.

As a long-term store of value, cash comes up woefully short. It presents a risk to the long-term investor far greater than any temporary decline in stock prices. Let’s go back to our loaf of bread example:

- After 30 years, inflation has driven the cost of the $5 loaf to $10. If your savings and investments merely keep pace with inflation, that loaf will effectively cost you the same.

- If you use dividends (that have grown about 2x the rate of inflation) to buy that loaf in 30 years, that loaf effectively costs you half as much, or only about $2.50 in today’s dollars.

- If you’ve held only cash for 30 years, that $10 loaf would effectively cost you nearly $20 in today’s dollars after the erosion of cash’s purchasing power. This effect spread across your entire budget would be devastating to your savings.

Regardless of the level of inflation – slow and steady, high, or anywhere in the middle – it will erode the value of cash.

Bonds – a Tool for a Purpose

The value of bonds cannot be overstated in a long-term portfolio designed to support a retirement. That is, provided they are of the correct types and used for the intended purpose. As has been the case for many topics, the last few months have provided a powerful and real-time example of the value of bonds.

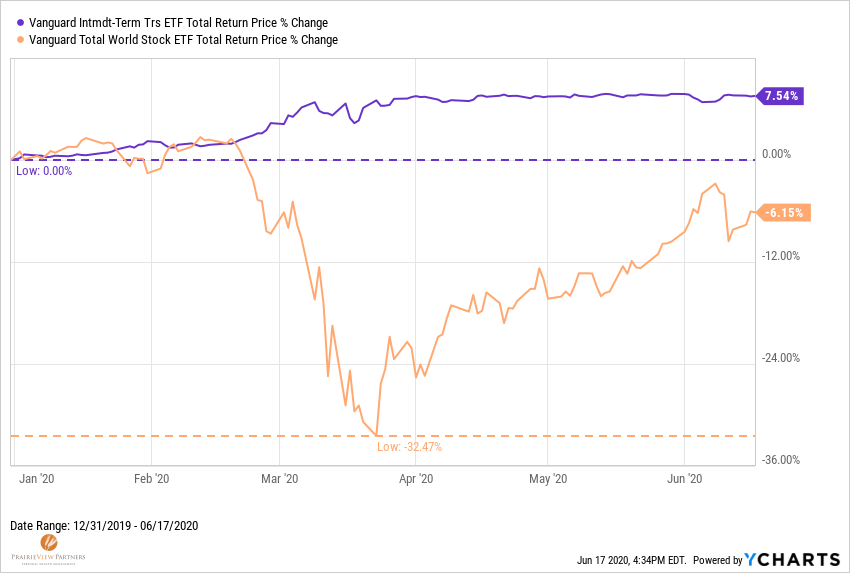

The chart below indicates the difference in return and path of return, year-to-date, of the Vanguard Intermediate Treasury ETF and the Vanguard Total World Stock ETF. For anyone wanting to make a withdrawal from a portfolio or rebalance when the stock ETF was down 32%, bonds provided the ability to do so.

But as with cash, a short-term experience, no matter how good, shouldn’t be extrapolated as a panacea. The fund in this example, on the surface most closely resembles the 5-year US Treasury note. Today’s yield to maturity on that note is 0.34%, which means that if you bought one today and held it to maturity you would earn 0.34% per year for the next five years and likely lose money after accounting for inflation.

This nearly assured after-inflation loss of value on a 5-year Treasury Note does not mean bonds should be wholly avoided. Thankfully, you, and most investors, do not own one singular 5-year Treasury Note. Let’s continue with the same Vanguard Treasury ETF example. This fund owns 119 different Treasury notes that mature anytime from tomorrow until ten years from now and average out to about five years. This presents an opportunity.

Without getting too far into the weeds (if you’ve made it this far you’re probably ready for the punchline), inflation and interest rates are closely linked over time – certainly not every day or even year. As interest rates rise (assuming that will happen again) the rolling maturities of a diversified pool of bonds allow new bonds with higher interest rates to replace those with lower interest rates. Further, owning these bonds that are relatively short-term in nature (5 +/- years) allows them to roll over into new bonds sooner when interest rates rise.

Yes, there is likely to be weaker returns from bonds as interest rates rise, but the foundation of rising interest rates is generally a stronger economy, which drives earnings, dividends, and stock prices higher. Over time, the return expectation on bonds such as these, is to exceed long-run inflation by only a small margin. The historical margin has generally been approximately 1% to 2%. So, the goal when buying the loaf of bread in 30 years is that it costs slightly less in real, or after-inflation, terms if you use your bond earnings to purchase it.

Myth Busting Gold as an Inflation Hedge

There is a long-standing belief that investing in commodities, principally gold, provides an effective hedge against the impacts of inflation. The basic principal of this belief seems to hold water. For a long period of our country’s history our currency was linked to gold, making for a more direct correlation between the value of the dollar and the price of an ounce of gold. Without a doubt, there have been times when this has worked, specifically the late 1970s and early 1980s during extreme inflation.

This relationship has been much weaker since then. Gold has become principally a speculative vehicle as it does not generate earnings and dividends or pay an interest rate. From a practical standpoint, a dollar invested in gold is one less dollar that could be invested in stocks or bonds. One less dollar invested in stocks is likely to reduce long-term return potential. One less dollar invested in bonds is likely to reduce bonds’ ability to provide a counterbalance to stocks’ temporary declines.

The Winning Formula to Beat Inflation

Perhaps it seems too simple. But it doesn’t need to be complicated. Stocks provide the best long-term opportunity for returns that exceed inflation, but they experience gut-wrenching temporary declines every so often. So, we want to own as much of them as reasonable with the rest of our portfolio in bonds. Done right, this will ensure we can hold all of our stocks during the declines, which enable us to earn their long-term benefit of returns well above inflation.

Understanding your goals that need to be funded, including which goals might be subject to different rates of inflation, is where thoughtful planning is required for portfolio construction and management so that even after inflation, your loaf of bread actually costs you less in 30 years.

Thanks for reading!

Matt Weier, CFA, CFP®

Partner

Director of Investments

Chartered Financial Analyst

Certified Financial Planner®