- April 8, 2025

Welcome to 2021! I’m sure nobody reading this needs me to remind them that 2020 was a difficult year and one that many would just as soon forget. I want to make the case that forgetting the investment events of 2020 – the lessons learned, theories validated, theories debunked, things we got right, things we got wrong, the way markets made us feel, and the results –would be a mistake.

Before getting into our investment lessons and market charts, I want to use this forum to extend a genuine thank you to clients and colleagues. I know I speak for many of my colleagues in saying that we had many very rewarding conversations with our clients despite difficult times. To both our long-time clients and those who placed your trust and confidence in us and joined our firm having never met us face to face – we are grateful.

In an odd way, being apart from our teammates brought us closer together through more intentional conversation and connection. We will also be sending out official announcements in the coming weeks introducing new team members. These individuals had courage to start a career in financial services, leave a long-time firm, and join a firm in Minnesota having never visited the state – all amid a most unusual interviewing and hiring environment. Financial markets have a way of humbling us, but they’re no match for the humbling power of the trust, confidence and dependability of our clients and colleagues.

Market declines happen when you least expect them

Try to place yourself back in January of 2020. Stock prices had more than recovered from the 2018 bear market. Unemployment was low and declining with the strength of the job market pulling people back in. The Barron’s Roundtable of top economists and market prognosticators predicted an average return of 8% for the S&P 500 for 2020 - it’s almost always 8%. It seemed to be the strongest and most sanguine market and economic environment since before the Great Financial Crisis. It felt like it was going to be a good year.

We don’t need to relive all the details and timeline of what happened next. The uncertainty about the economic impact of the virus gave way to 33 days of the most intense volatility and fastest ever trip to a 20% decline in the S&P 500. And it kept falling to produce the fastest ever decline of more than 30%.

We often mention that the next recession or bear market will not be caused by the same factor as the last one. Its cause will be random and unpredictable. At least in many cases there is some underlying weakness in the economy. The Fed gets a little ahead of itself in raising interest rates, or the housing market implodes (more on this later). The 2020 market decline, however, was quite possibly the most random and exogenous shock the global economy has faced.

After 33 days of what might be best described as sheer terror in financial markets – even Warren Buffett sold! – a diversified stock portfolio closed 35% off its February peak on March 23rd. Then on March 24th, we had a 9% jump. The previous 9% increase in stocks – a mere seven trading days earlier – was followed by a 12% decline the following day. Not this time.

Market declines happen when you least expect them – Part 2

Now try to remember back to late March. How did you feel then? Maybe you had an inkling that the bottom in stock prices was near, but even if you thought that was the case, it’s understandable if you didn’t have much conviction in that stance. It’s also understandable if you thought stocks had farther to fall. Weekly job losses were in the millions!

What started on March 24th ended the fastest decline of more than 30% ever in stock prices and marked the beginning of the fastest recovery back to a previous peak. Stocks started rising while the virus was still spreading, unemployment was increasing, and fear about financial markets was at an all-time high – higher than at any point during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).

How could stock prices stop their free-fall and start rising so quickly when the situation was still getting worse? There are several answers to this. When viewed individually, these answers can seem simple, but in combination, they highlight the complexities of our economy, markets, and behaviors. All of them are individually necessary but only collectively are they sufficient.

- The Federal Reserve: The Fed learned from the GFC and acted quickly and boldly in providing liquidity and backstops to markets. Yes, there were some rough days in markets, but there was never real concern over the stability of banks, money market funds, or lending facilities.

- Congress: Everyone likes to pick on Congress for not getting things done, but this time around they came to agreement quickly to support individuals and small businesses. It’s easy to poke holes in exactly what they did, but like the Fed they learned from the GFC that speed to solution is important.

- Technology: Many businesses and workers were able to pivot to remote work, online order fulfillment, and expand delivery networks in ways that wouldn’t have been possible at any other time in history. This allowed many more people to work to support themselves, their customers, and the economy than had this happened even ten years ago.

- Strong economic fundamentals prior to the shock: Households and businesses were in better financial condition at the onset of this crisis compared to a time like the lead up to the GFC. In the latter scenario, there were fissures in the economy that made matters worse and delayed the recovery.

- Signs of improvement: Despite the fact that things were bad and getting worse at the end of March, things were getting worse at a declining rate. This is where expectations enter the picture. Investors often extrapolate the present into the future. Think of it this way: if a company has been losing money for years and then one surprise quarter it announces that instead of losing a million dollars, it only lost half a million dollars and in a few quarters it’s likely to breakeven, it’s stock is likely to soar.

- The forward-looking nature of markets: Markets are “discounting” mechanisms in the sense that they look to the future – usually six to 18 months – and attempt to reflect those expectations in current prices. In the first half of March the expectations were bad and getting worse. By early April, expectations about the future were bad but getting better.

All of these factors set the table for what turned out to be nothing short of a remarkable recovery in stock prices through the end of the year. But as there was no clear “Sell Now!” indicator in February, there was no clear “Buy Now!” indicator in March or April. And despite stocks posting 70% returns off their bottom through the end of the year, it certainly wasn’t easy sailing along the way. It also doesn’t mean you need to agree with the market’s interpretation of conditions.

Less than a month after stock prices started rising, there was still so much dislocation in the economy that the price of oil turned negative. Meaning, oil producers would pay someone to take it off their hands! Our economy is not designed for people to stop driving, flying, shipping goods, and running factories overnight. Stock prices mostly took that in stride and kept rising through the spring and in into the summer. This doesn’t fit our expectations of what is supposed to happen when stock prices are recovering.

What happened with oil prices in the spring while stocks were recovering off their lows highlights one of many examples that show not every recession is the same as the last one. Our expectations are influenced by our experiences, but no two experiences are the same – especially when it comes to recessions and bear markets.

This isn’t what is supposed to happen during recessions. Or, is it?

What if I told you back in early 2020 that during the next recession, we would have the strongest housing market in nearly 15 years, the personal savings rate would increase, retail sales would be higher by the end of the year than they were the previous year, and we would have the best year for Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) of stock since 1999? You might think that I was reading some fringe economic reports and maybe even stop reading these posts. This is one of many reasons why predictions are so dangerous.

By the time we were three quarters of the way through the year, the S&P 500 had reached several new record highs and US household net worth reached a record high. Improved household balance sheets, high income earners’ ability to keep working, and low interest rates spurred housing demand. Retail sales have been supported by stimulus programs plus a quickly declining unemployment rate from the springtime peak of over 14%. Stocks continued looking to the future and, while certainly still showing weakness, our economy began adapting. None of which were expected only six months earlier.

The recession and accompanying bear market has played out so differently than every prior recession that it would have been impossible to predict its trajectory at any point along the way. There was fear at the onset of the pandemic that the economic fallout would be as bad as the Great Depression. That outcome would assume that our institutions, such as the Fed, have not learned from past events. It would also assume that our economy, technology, and science also have not adapted over time.

To be sure, many parts of the economy remain in difficult situations and we are not out of the woods yet. But, as the probabilities of worst-case outcomes became remote, markets could again look to the future and what a recovery may look like in coming years. As the recovery’s momentum built in the closing months of the year, we ended with results that would have been considered remote possibilities less than a year ago.

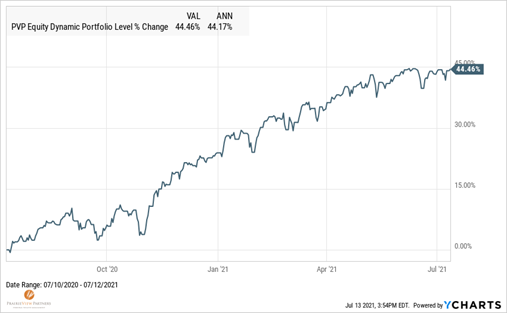

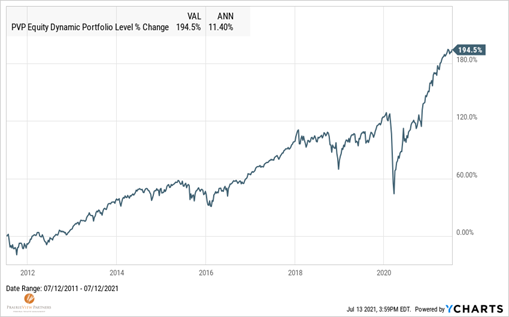

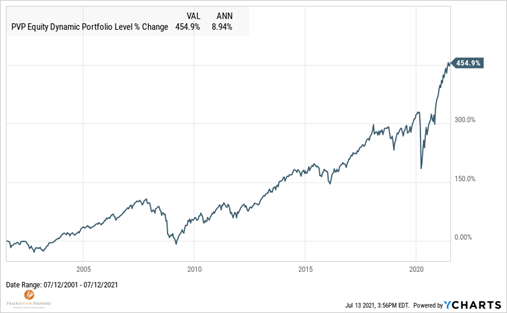

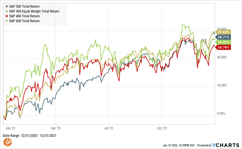

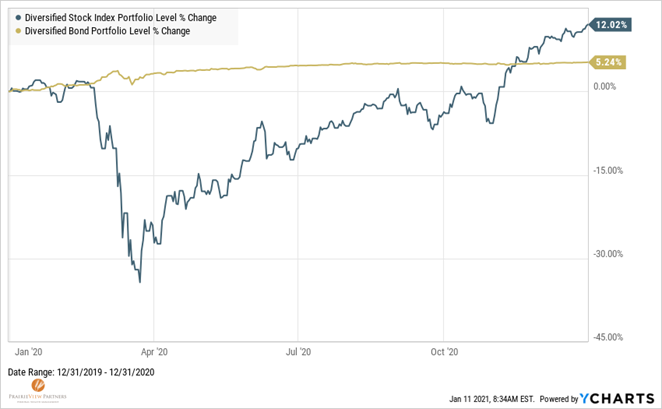

Tallying the 2020 market score

When the books were closed on 2020, a diversified portfolio of stocks ended the year with a total return of 12%. The S&P 500 closed the year up 18% including dividends. Most of its leadership was due to stronger gains earlier in the year as Small Cap Stocks and some international categories – particularly Emerging Markets as Chinese stocks were some of the global leaders in the second half of the year – led markets higher as the recovery picked up momentum. In fact, the Russell 2000 small stock index posted its best monthly return ever during November 2020.

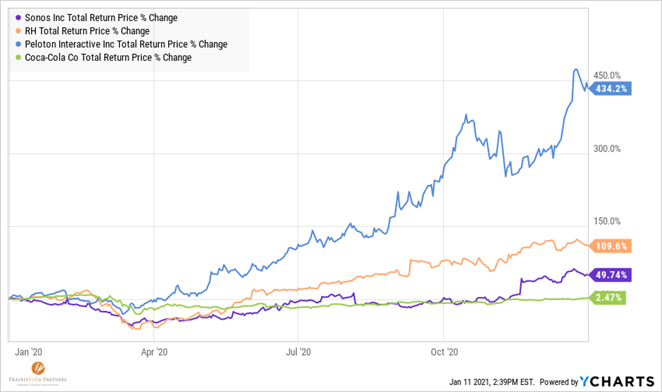

On cue, much was written about how diversification once again failed investors in a bear market. These messages fail to properly define diversification, confusing it with asset allocation. Diversification provides protection from the unknowable future fortunes of risky assets, i.e. which individual stocks, sectors or countries’ markets might perform better or worse in various economic environments. One form of “conventional wisdom” for investing in recessions is to favor “defensive” stock, such as oil or energy companies because everyone still needs to put gas in their car, and shun technology stocks that depend on strong business and consumer spending. How would the “conventional wisdom” have worked in 2020? Let’s just say this is one of the areas where diversification continues to be invaluable.

In another example, after experiencing the GFC, it would have been hard to predict that in the next recession consumers would run out and spend more than ever on furniture, $2,500 stationary bicycles, and smart home audio systems. Take a look how Restoration Hardware, Peloton, and Sonos fared compared to the traditional “recession proof” stock of Coca-Cola.

We’ll count these as more wins for diversification over predicting recession-beating stocks. But, what many incorrectly conclude is that diversification is intended to protect investors from declines in prices of stocks in times of crisis. That conclusion is not only wrong it is misleading and can be dangerous. This is where asset allocation, or how much of one’s portfolio is invested in “risky” versus “safer” assets, becomes most valuable. As with diversification, when properly defined, I can assure you, that proper asset allocation also most certainly proved to be a winning strategy in 2020.

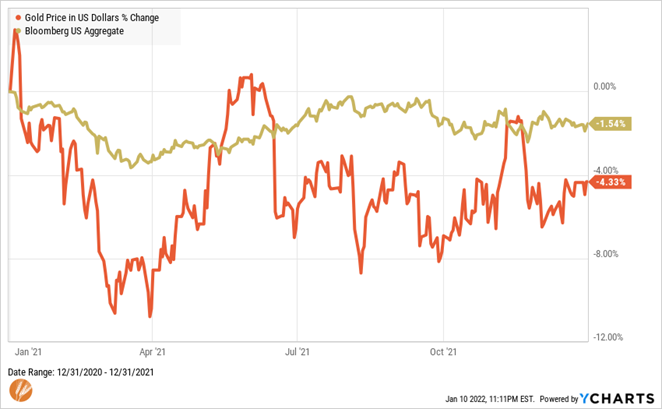

In the midst of the most tumultuous times in early 2020, a diversified portfolio of high-quality bonds not only experienced less price fluctuation than stocks, they actually posted positive total returns. This behavior differential of bonds offered three benefits: strong performing capital to fund withdrawals, a source of additional capital to “rebalance” into stocks, and a source of confidence that your portfolio wasn’t experiencing the full brunt of the daily stock fluctuations.

Of course we’ve all heard stories about the gains of Tesla and Bitcoin in the recent year as if, like Restoration Hardware or Peloton, their fortunes could have been known ahead of time. The general theme that stocks recovered after a panic-induced decline remained the same as in the past. However, the more specific one gets in looking at individual sectors or companies, the more the fortunes differ from one economic event to the next.

Diversification ensures that we’ll own whatever stocks prove to be most fortunate regardless of the shape of the recovery, but asset allocation, or ensuring that your risk matches your goals, ensures that we can earn the benefit of continuing to own a diversified portfolio of stocks.

Where do our investments go from here?

Prediction season on Wall Street is again upon us and the Barron’s group’s average forecast for the S&P 500 is for a 9% gain this year. That says nothing of what might happen along way, what surprises we might encounter, or how investing might make us feel this year.

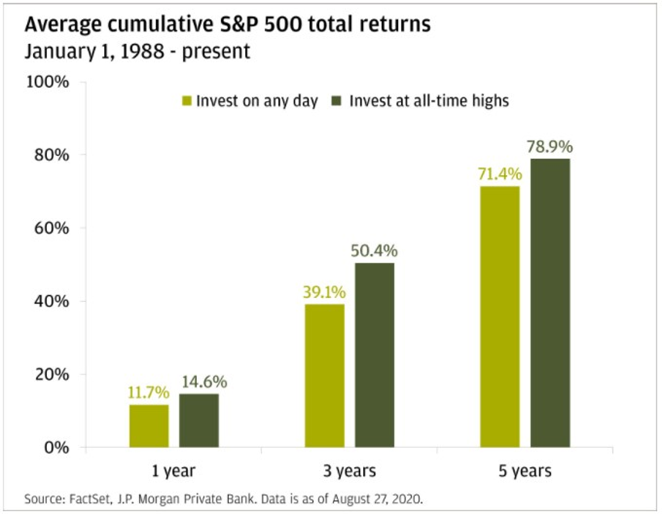

The S&P 500 achieved more than 30 new all-time high-water marks from August through the end of 2020 amid a recession and pandemic and after enduring a 34% decline during the year and difficult Presidential election. Understandably, it leads many to question whether it is a good idea to commit new capital to stocks at market highs.

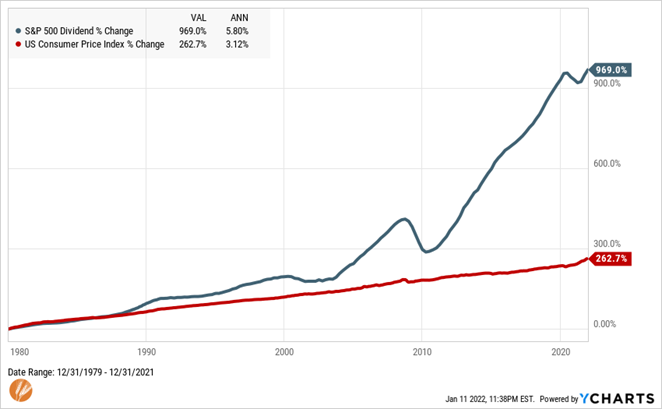

If we wait until no risks are present before investing, we will never make an investment. There are always risks involved – real or perceived. The specific risks will vary through time, but their presence is precisely why stocks provide us with the returns they have over time. Without the risks, their returns would be the same as Treasury bills. As it turns out, investing at all-time highs tends to be a pretty successful time to invest.

Regardless of the market environment, time in the market will always beat timing the market when given sufficient time. This, of course, is easier to accomplish with the right plan for your investments that ensures your portfolio’s risk matches its needs.

What did we learn from 2020’s market volatility?

The year 2020 provided quite possibly the most striking evidence available that random, rather than expected, events cause stocks to decline. This reminds me of a statement made by Howard Marks, one of my favorite financial writers, that “you can’t predict, but you can prepare.”

The stock market will provide us with attractive returns relative to their risk provided we stay invested for the long-term. But, it doesn’t always make it easy on us. It doesn’t care when we want to retire, when we need to pay for our kids’ college, or when we want to buy a second home near the beach or the mountains. It also doesn’t care if declines turn the corner and start advancing before we have the wherewithal or courage to commit more capital at lower prices.

All crises are different and, aside from preparation through planning and ensuring your portfolio reflects your goals and circumstances, there is no certain playbook. If you haven’t planned before a crisis hits, it’s too late. In the GFC it took 16 months for stocks to hit bottom and four years to recover their previous peak. This time it took 33 days to hit bottom and only five months to recover their previous peak. Just think, by the time this hit your inbox if it was 2008 (or 2009), stocks would still be on their downward path. We would have been prepared for that, too.

As someone who enjoys the other side of the story, I found a fascinating piece about a few successful predictions that are almost frighteningly true. In 1921, Charles Steinmetz, a.k.a. “The Wizard of Schenectady” predicted the following would be true in 100 years from then:

- The same electrical apparatus that heats our homes would also cool them and keep the humidity level.

- We would consume our entertainment in our homes.

- Our vehicles would be powered by electricity.

Air conditioning, Netflix, and Tesla – proof that things do get better over time as innovation is allowed to flourish.

Matt Weier, CFA, CFP®

Partner

Director of Investments

Chartered Financial Analyst

Certified Financial Planner®